The Working Life of Turvey: Occupations Through Time

What might a local historian in the future discover about the working lives of people in Turvey at the time when the Turvey History Society was established? They might find twenty-first century jobs such as IT consultants, ‘wellbeing’ coaches or Amazon delivery drivers. But some of today’s occupations have had a much longer history in the life of the village – for example farm workers, butchers and shop keepers, the clergy, and, of course, ‘alehouse keepers’ in The Three Fyshes and the Three Cranes! Continuity and change is the story of local history, and of Turvey.

Discovering the past through occupations

Just as the jobs that Turvey people do today can tell us much about our present society, exploring occupations in previous periods tells us much about life in the village in the past. Thomas Pierre, for example, was a Turvey lacemaker who took on Susan Goodwin, ‘poor child’, to be his apprentice in 1671. Nearly two hundred years later there were 142 women and 36 female children recorded as lace-makers in the 1851 census. Blacksmiths were recorded in the early nineteenth century but by the 1870’s there were railway navvies building the railway. The changing nature of employment reveals a wealth of stories. Just these examples alone can tell us about the support of poor families, the important role of women and children in the economy of agricultural households, and how transport was transformed in the nineteenth century.

Census returns are a good source of information for finding out what work people did in the past. The first national census was conducted in 1801 but it wasn’t until the 1841 census that more detailed information on each individual in every household on census night, including occupations, began to be systematically recorded.

To find out what people did before then is more difficult but still possible. From 1812 Anglican Parish registers were required to record fathers’ occupations at baptisms and even before that date, church burial and marriage registers can be a useful source of information. Other documents such as wills, apprentice indentures, letters and diaries often also reveal something about how people earned a living.

What do these sources tell us about the past occupations of people in Turvey

Prayers for the dead and testing the ale

The All Saints Burial Register for the eighteenth century records some occupations and this provides fascinating insights, not only into that period, but also gives us glimpses back into medieval life. A bedesman appears in the register in 1749, 1763, 1781 and 1791. This term has medieval origins but later came to mean someone in receipt of alms. Before the Reformation of the sixteenth century, people were encouraged to believe in Purgatory, a place between Heaven and Hell, and it was thought that prayers for the dead could assist the passage of souls through Purgatory to Heaven. Bedesman were people, often the poor of the parish, appointed to pray for the souls of a deceased benefactor. The puzzle is how this title come to be associated with people in Turvey over 200 years later.

According to the Archivist of Brasenose College, Oxford, the answer lies in the 1570 will of John Mordaunt, Lord of the Manor in Turvey. The Mordaunts remained faithful to the Catholic Church, even after the Reformation. In his will, John Mordaunt left property to the College, then in Essex and London, and in the terms of the will required the College to pay ‘eyght pence’ every Sunday to each of four poor almsfolk of Turvey, or £6 18s. 8d. yearly, to pray for his soul. The College’s Bursar’s records show these payments were still being made to ‘bedesmen at Turvey’ in the eighteenth century. The requirement to pray for John Mordaunt was no doubt long forgotten, but four poor parishioners were still being selected, probably by the vicar, to receive the 8d a week. The title bedesman was not really an occupation, therefore, more a description of social status.

The Burial Registers for 1758 and 1766 record the deaths of ale conners. Documented from the fourteenth century, ale conners were appointed annually by a special manorial court called a court leet. Their job was to visit ale houses, testing and certifying the quality of the ale, and in some cases they were authorised to fix the price. If the ale was of poor quality, the ale conner could summon the brewer to the manor court for judgement. Perhaps one of the more desirable jobs of the time! Or perhaps not, given the risks to health of unsound beer or of becoming unpopular in the local community if the beer was not to the ale conner’s taste!

Self-sufficiency in the village: the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

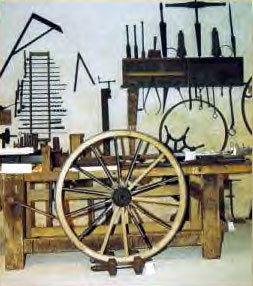

Up until the late nineteenth century most people in rural villages such as Turvey would have worked in the village and its surrounds. The majority worked on the land, most as agricultural labourers in the arable fields, for owner or tenant farmers. Some worked as stockmen looking after the animals. Others produced goods and services, mostly for the use of the local community or for trading within the area. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, in addition to wills left by yeomen and husbandmen (owner and tenant farmers), and one ‘gentleman’, there are wills of a miller in Turvey in 1554, a wheelwright in 1584, a minister in 1607, a shoemaker in 1608 and a tailor and an inn-holder in 1609. The vast number of poorer people, the cottagers, would not of course have had sufficient money or property to warrant the writing of a will. Godber (writing in1969) estimated the parish’s population around 1600 to have been about 500, only 17 of whom had been taxpayers in 1597.

Fifty-two seventeenth century Turvey wills give occupations. Whilst these again are not representative of the whole population, they give a flavour of who had sufficient wealth to justify a will. The majority (28) are yeomen and husbandmen. Yeomen were generally higher in social standing than husbandmen and often, although not always, owned more land. The remainder are tailors (4), carpenters (3), blacksmiths (2), shoemakers (2), a baker, a spinner, and a metalman. The goods made by local craftsmen would have been sold in the village or perhaps in the markets at Harrold or Olney. The upper classes are represented by the wills of two ‘gentlemen’. A minister, who would then have been university educated, is also recorded in 1607.

Edward Plasterer made a will in 1618. Contrary to his name, he was, in fact, a fuller, whose job was to prepare wool for spinning and weaving. This was done by using a compound called Fuller’s Earth to remove the natural oils and dirt from the wool. Sheep farming was an important part of the rural economy in sixteenth and seventeenth century England and there is evidence of bequests of ewes and lambs in the 1550’s wills of Turvey’s Roger Sprote and William Ball. Mr Plasterer would therefore have been called upon by local farmers to work on their fleeces.

The occupations revealed in the wills are typical of rural England at the time. There is also evidence of more specialised local employment. In North Bedfordshire, pillow lace making had developed in the villages on the Great Ouse in the early 1600’s, and there is evidence of lace buyers in Turvey in 1680 (Spenceley, 1973). To begin with, men, like Thomas Pierre, made lace, often when agricultural labour was slack, but over time lacemaking came to be an occupation for women and children, whilst the lace dealers who provided the patterns and bought and sold the finished lace remained the province of men.

Lacemaking continued as a significant occupation for Turvey women until the nineteenth century. The significance of lace making locally in the seventeenth century is illustrated in the brief mention of ‘Turvoy’ by the renowned travel writer Celia Fiennes. Unusual for a woman of her time, she travelled extensively in the late 1690’s and documented her experiences. Travelling from Bedford to Northampton she writes ‘Ye great road Comes in good way, thence Turvoy 5 mile belonging to the Earle of Peterborough where he was. They make much bonelace in these towns’.

Self-sufficiency in the village: the Eighteenth Century

In the eighteenth century, the All Saints Burial Register records: shepherds, labourers, a ploughwright (maker of ploughs), a gelder (who castrated animals), stonemasons, carpenters, thatchers, a plasterer, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, a limekiln man, cordwainers/shoemakers, a cutler, a cooper (barrel maker), tailors, lace dealers and lacemakers, bakers, butchers, shopkeepers, a poulterer, soldiers, a schoolmaster, servants and, of course, ale house keepers! Village self-sufficiency indeed!

Bibliography and Sources

Bedfordshire Archives, Apprenticeship papers, Thomas Pierre, P27/14/1.

BedfordshireHarriet Archives, Register of baptisms, marriages and burials, P27/1/2.

Bedfordshire Archives, Index of wills.

Bedfordshire Archives, Will of Roger Sprote, ABP/R12/121d.

Bedfordshire Archives, Will of William Ball, ABP/R13/113.

Godber, J., History of Bedfordshire (Luton, Bedfordshire County Council, 1969).

Spenceley, G.F.R., The origins of the English pillow lace industry, The Agricultural Review, 21(2) (1973), pp.81-93.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page