Turvey Bridge, spanning the River Great Ouse, is the distinctive entrance to the village from the west, and forms the boundary between Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire. It has been an important factor in the development of the village, providing links to the east and west; its history is described in Turvey Bridge – A Brief History | Buildings, Monuments and Features | Turvey History.

From Tudor times, an Act of Parliament of 1555 required each parish to take responsibility for keeping their roads repaired. Every man in the village who owned or occupied land worth £50 a year or more was supposed to supply a cart and horses, tools and equipment for the repairs, and the services of up to two men to work for six days a year.[1] A ‘Surveyor of Highways’ was appointed from the members of the Parish Council, and it was his responsibility to get any money needed for the repairs from the chief landowner. The Act was amended in 1563 and 1575 and repealed in 1835. [2]

By the 18th century, the road formed part of a major route from London to the North, and so it was important for both local people and longer-distance travellers that it was kept in good repair. Over its life, responsibility for its maintenance has been the subject of legal proceedings on at least five occasions, and in one became a landmark case, defining how a new law should be interpreted.

1560

The earliest reference we have to maintenance of the bridge is in the 1560 will of John, first Lord Mordaunt, who left £40 for the maintenance of the part in Bedfordshire, and £26 12s 3d for the part in Buckinghamshire. Lord Mordaunt would have been responsible for funding any repairs in his lifetime.

1673

The Lock Gate[3] magazine (1964) briefly mentions an early dispute over responsibility for the maintenance of the bridge

‘at the Summer Assizes in 1673 the whole County of Bedford was indicted because the bridge was out of repair, and the Grand Jury returned “a true bill”’.[i]

A ‘true bill’ was the endorsement made on a bill of indictment by a grand jury certifying it to be supported by sufficient evidence to warrant committing the accused to trial.[4] The grand jurors at the assizes were between 14 and 23 gentlemen of high standing in the county. Once they were sworn in, the judge at the assizes would direct their attention to the points in the case to be considered, and they would then retire with the bill of indictment (the formal written accusation) and examine the witnesses for the prosecution. If at least 12 of them thought that the evidence was sufficient to warrant a trial of the accused, the words ‘a true bill’ were endorsed on the back of the bill.

The grand jury’s functions were gradually made redundant by the development of committal proceedings in magistrates courts from 1848 onwards and were entirely abolished in 1948. [5]

1731

The first legal case for which we have details, from 1731, is recorded in a manuscript found in a collection of papers belonging to All Saints Church, believed to have been compiled by Rev G.F.W Munby, Rector of Turvey 1869-1905. The case is described

‘Turvey Bridge in the County of Bedford the only passage for Coaches, Carriages over the River Ouse there, are becoming ruinous and without the least fence by wall or rails, at Summer Assizes in 1731, An indictment was found against Charles Earl of Peterboro’ for not repairing the same Ratione Tenure.’[ii]

An indictment is a criminal accusation that a person has committed a crime[6]; Ratione Tenure means ‘by reason or in respect of his tenure’. [7]

It is not clear whether this was simply a financial matter, as the Earl as principal landowner had responsibility for funding the repairs or was also because he had not provided the labour as required by the 1555 Act.

The question asked of the judge, Sir Thomas Abney, was whether fencing of the bridge was essential for safety reasons, and how the owner, being a Peer of the Realm and living outside the county, could be indicted and the failure remedied. By this time, the Mordaunts had left the village and made Drayton Hall in Northamptonshire their principal seat.

Abney’s answer was that fencing was to be considered as a necessary part of the repair of the bridge and issued the Indictment. On the subject of the Earl’s being compelled to appear despite being non-resident, he stated ‘Peers have no priviledge in Treason, felony or trespass and consequently the defendant has no priviledge in the present case’.[iii]

Following this, applications were made to Lord Raymond, Chief Justice, and subsequently Lord Hardwick (later Lord Chancellor) for a summons of the Earl. However, ‘neither cared to grant one against the defendant as he was a Peer but both advised an Indictment against the inhabitants of Turvey for not repairing the bridge… so the matter has slept and nothing more been done in it for soon after Lord Peterboro’ promised to refer it to Counsel, but his Lordship died before such reference took place’ [iv]

So, no action was taken to provide fences or rails on the bridge; Charles, Earl of Peterborough died in Portugal in 1735 and only returned to Turvey to be buried in the family vault at All Saints Church.

1738

Portrait of Thomas Parker (1695-1784), English judge by John Tinney

From the same document, we find that in 1738 a second application was made, again about the lack of fencing on the bridge. The question put to Judge Thomas Parker was

‘Admitting the said Bridge has never been fenced, yet is not the fencing thereof to be looked upon as a necessary part of the repair of the said Bridge for the safety of the subject, and will not an Indictment or Information be for want of such fencing only and the Person charged with the repairs of the said Bridge be compelled to fence the same.’[v]

Parker’s answer was that fencing was necessary for safety, but although the Mordaunts, Lords of the Manor of Turvey had taken responsibility for repairs, the bridge had never been fenced, and so they could not be held liable for putting it into a better condition; they were only responsible for maintaining its current structure.

Thus, seven years later Judge Parker appears to have overturned Judge Abney’s decision that the bridge should be fenced.

Turvey Bridge in 1839

1795

The Mordaunts sold the Turvey estate in 1786. In 1795 the river froze, then flooded badly on thawing, and caused the fourth arch to collapse. There was some uncertainty whether the sale had transferred the maintenance responsibilities to all the purchasers of the properties, or to the Lord of the Manor, in which case John Higgins would have been solely liable.

To resolve this, the purchasers arranged for a case to be brought at Quarter Sessions at Cambridge Assizes in 1795 and 1796. Searches for evidence in the sale particulars to support the case proved fruitless; the case was adjourned, and eventually not proceeded with. John Higgins, who was at that time surveyor of the turnpike road, organised the repair of the arch; the costs were met partly by the Turnpike Trustees, partly by the parish and partly by those who had bought the Mordaunt lands.

1824

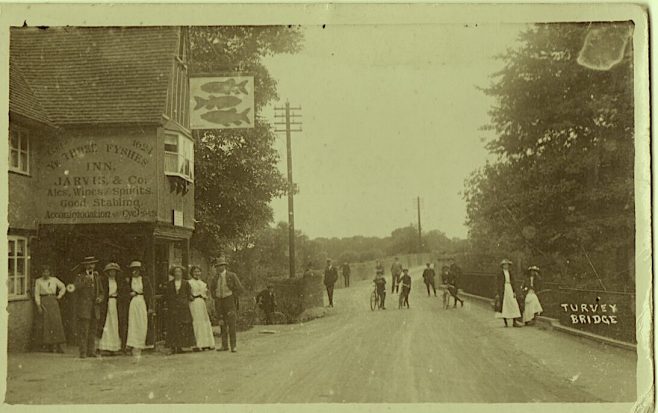

Responsibility for the maintenance of the bridge was again in dispute in 1824. The case ‘Rex v. Inhabitants of Bedfordshire: Turvey Bridge’ was heard in Cambridge as Col Higgins of Picts Hill, John Higgins of Turvey Abbey and Thomas Higgins of Turvey House were magistrates and interested parties in the dispute. Documents recorded ‘…The said bridge… is very ruinous, broken, dangerous, and in great decay for want of upholding, maintaining, amending, and repairing the same, so that the liege subjects of our said Lord the King upon and over the said Bridge with their Horses, Coaches, Carts and other Carriages could not during the time last aforesaid nor yet can go, return, repass, ride and labour as they before used and were accustomed to do and still of right ought to do without great danger of their lives and the loss of their goods to the great damage and common nuisance of all the liege subjects of our said Lord the King….’.[vi] William Ingram, Landlord of ‘Three Fishes Inn’ was a witness in the case. The previous responsibilities of the Earl of Peterborough for maintaining the bridge were again cited, and it appears that, as in 1795, the private owners and the Turnpike Trustees were found responsible for the costs. There is no record of public money being used to effect the repairs.

Turvey Bridge from the Mill

1878

The Northamptonshire Mercury, Saturday 18 March 1878, included a full report of the judgement delivered in the Court of Queen’s Bench, Westminster, relating to responsibility for maintenance of the bridge. It was reported as ‘an important case affecting the interest not only of two neighbouring counties, but of counties in general. The case is important also as being one of the first decisions under the recent Act of Parliament relative to highways discharged from Trust Management.’ [vii]

The Bedford to Olney Turnpike Trust had been wound up in 1874. About two years before this, some of the arches on the Buckinghamshire side were washed away by a flood; the trustees made a temporary repair. When the Trust was wound up, the dangerous nature of the structure was reported to the Clerk of the Peace for Buckinghamshire (who was responsible for the records of quarter sessions, framing of indictments, and also had administrative duties including ordering the repair of bridges). The intention was to obtain an order for its reconstruction to be issued by the Quarter Sessions for Buckinghamshire. The former Trust denied liability, so ‘some influential gentlemen in the neighbourhood took upon themselves the expensive process of indicting the county of Buckingham’. [viii]

A hearing of the case, The Queen v. the county of Buckingham, took place on 14 February 1878 in the Queen’s Bench Division, under Lord Chief Justice Cockburn and Mr Justice Mellor. Cockburn was famous for hearing some of the most controversial cases of the nineteenth century, including murder, terrorism and obscenity, and often sat with Mellor.

Chromolithograph, portrait of Sir Alexander Cockburn, Lord Chief Justice (d. 1880), published by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London

Caricature of The Hon Sir John Mellor. Caption reads “Judges the Claimant”.The Act of Parliament that dissolved the Trust made provision for all the bridges previously built by the trustees to become county bridges and repaired as county property.

Buckinghamshire’s argument was that the 1790 Turnpike Act related to the bridge as it existed then – the trustees had constructed the new arches on the Olney side after this date – and responsibility for maintenance of the new part did not pass to the county on the dissolution of the Trust.

Buckinghamshire’s Counsel, Mr Merewether, argued that this meant that the bridge had to have been built strictly within the power of the turnpike trust, and this was not the case for the arches in question.

Cockburn stated ‘When those two new arches were added to the former bridge it becomes one entire construction. It seems to me vain to say that you can distinguish those two arches as forming a part of one whole entire bridge from one bank of the river to the other.’ He continued ‘All that is required [by the Act of Parliament] is that the bridge shall be repaired and this is the case here’. [ix]

Having established that the bridge was a single entity, Cockburn went on to address the question of responsibility for the repair. Merewether had argued that before the arches were built, there were individuals who were responsible for repairing the highway, as it then was, and that they should continue to have that responsibility, even though the highway was now a bridge. Cockburn agreed that the liability for repair of the highway would be ‘enlarged’ by having to keep the bridge arches in repair as well but ruled that liability had been discharged by the Act of Parliament which dissolved the Trust; this passed the burden of repair to the county.

Cockburn continued ‘The bridge is for the common benefit of both parties, and it is as much to the interests of the inhabitants of Buckinghamshire to have a communication with the adjoining county across this bridge into Bedford as it is for Bedfordshire to have a communication with Buckinghamshire. ‘ [x]

The important part of the judgement, which sets a precedent for similar cases is then given:

‘A bridge is liable to be repaired by two counties, unless there is something to distinguish the case from the ordinary presumption of law, they are bound to repair ad medium filum, and because there are persons on the other side of the arches, who are liable to repair, ratione tenurae, who are liable to the rest that does not take away the liability to repair so much of the bridge that is in this county.’[xi]

The ad medium filum rule is the legal presumption that states where the boundary between two properties lies either side of a highway or non-tidal river or stream, the boundary runs down the middle of the highway, river or stream.[8]

Mr Justice Mellor agreed and confirmed ’…all turnpike roads which shall now become ordinary highways, and which have therefore been repaired by trustees, shall become county bridges and be repaired accordingly’. [xii]

Following this judgement, work was put in hand to rebuild the western approaches, and was completed in 1880, when the County formally took over responsibility for the maintenance of the bridge.

Turvey Bridge 1919

[1] The Eighteenth Century in Turvey | Turvey Through Time | Turvey History

[2] Roads | VCH Explore (victoriacountyhistory.ac.uk)

[3] The Lock Gate was the journal of the Great Ouse Restoration Society, 1961-1977. The Society was formed to accomplish the restoration of navigation of the river from Bedfordshire to The Wash. The Bedford River Festival in 1978 celebrated the completion of the project.

[4] Collins English Dictionary Copyright © HarperCollins Publishers

[5] Grand jury – Wikipedia

[6] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “indictment”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 Oct. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/indictment. Accessed 14 September 2021.

[7] The Law Dictionary – Black’s Law Dictionary Free Online Lega Dictionary 2nd Ed.

[8] The ‘ad medium filum’ rule | Legal Guidance | LexisNexis

[i] The Lock Gate magazine

[ii] Manuscript compiled by Rev G.F.W. Munby

[iii] Manuscript compiled by Rev G.F.W. Munby

[iv] Manuscript compiled by Rev G.F.W. Munby

[v] Manuscript compiled by Rev G.F.W. Munby

[vi] The Bedfordshire Times and Independent Friday 13 June 1930

[vii] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

[viii] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

[ix] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

[x] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

[xi] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

[xii] Northampton Mercury Saturday 18 March 1878

No Comments

Add a comment about this page